VOC

An artists’ book by Clifton Meador

Printed by offset lithography, case-bound book

Edition of 100

2022

I was, like so many other people, stuck at home during the Pandemic. In addition to the relentless doom-scrolling of reading infection and mortality figures, I spent time looking at the websites of museums I could no longer visit.

One site was particularly well designed and user-friendly: the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. As I clicked through the images of paintings, furniture, flatware, guns, metalwork, objets de vertu, coins, glass, and silver, I started thinking about the Netherlands in the 17th century and the vast wealth that was evidenced in the Rijksmuseum’s collections. I started reading about the Dutch East India company.

Chartered in 1602, the Dutch East India company—or in Dutch, Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie, referred to as the VOC—was the first publicly traded corporation in the world. The VOC was established to commercialize the highly profitable spice and silk trade with India and the East Indies by spreading the risk incurred by individual ships attempting the long and perilous voyage to the East. The VOC aggregated the costs and then distributed the profits (and the losses) of many separate voyages, eventually creating a source of immense wealth for its investors. The VOC became a multinational company-state, perhaps the largest commercial organization in history, with its own military forces, fortresses, and quasi-independent city-states across South Africa, India, and the East Indies. The VOC was able to independently wage war, coin money, negotiate treaties, establish colonies, enslave people, massacre Indigenous populations, and create spice monopolies by burning entire islands clear of any spice plants.

The so-called Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century contained massive contradictions: a society that exported extensive, violent colonialism, while at the same time supporting many creative practitioners, allowing relative freedom of the press, and providing tolerance for some level of dissent. In this project I focused on using the collection of the Rijksmuseum to suggest this contradiction and to tell, using only objects from this collection, the story of the birth of the VOC and the resultant wealth of the Dutch Republic. My goal was to show how luxury goods, still life paintings, metal work, objets d’art, portraits, and weapons were the product of an extractive colonialism.

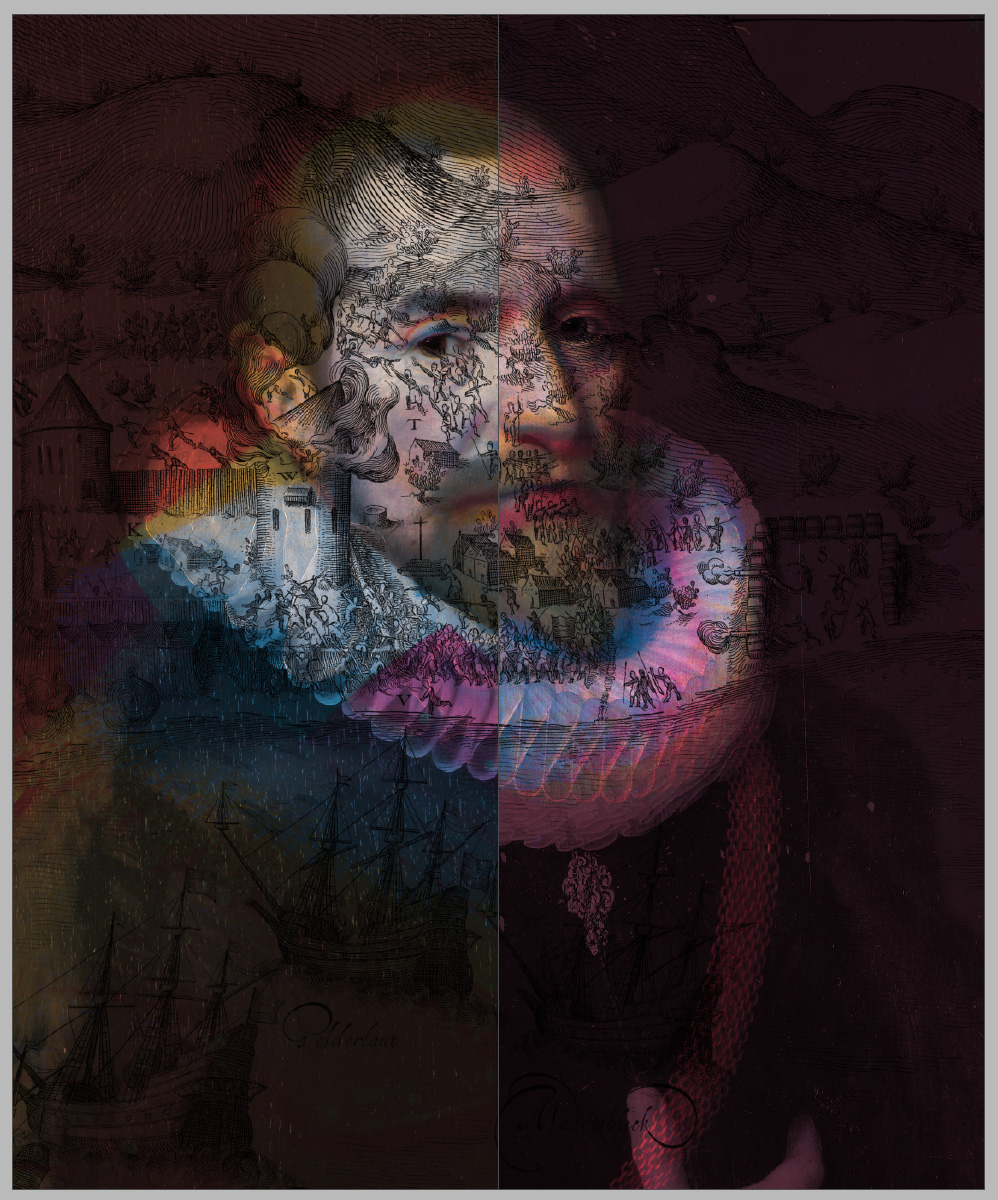

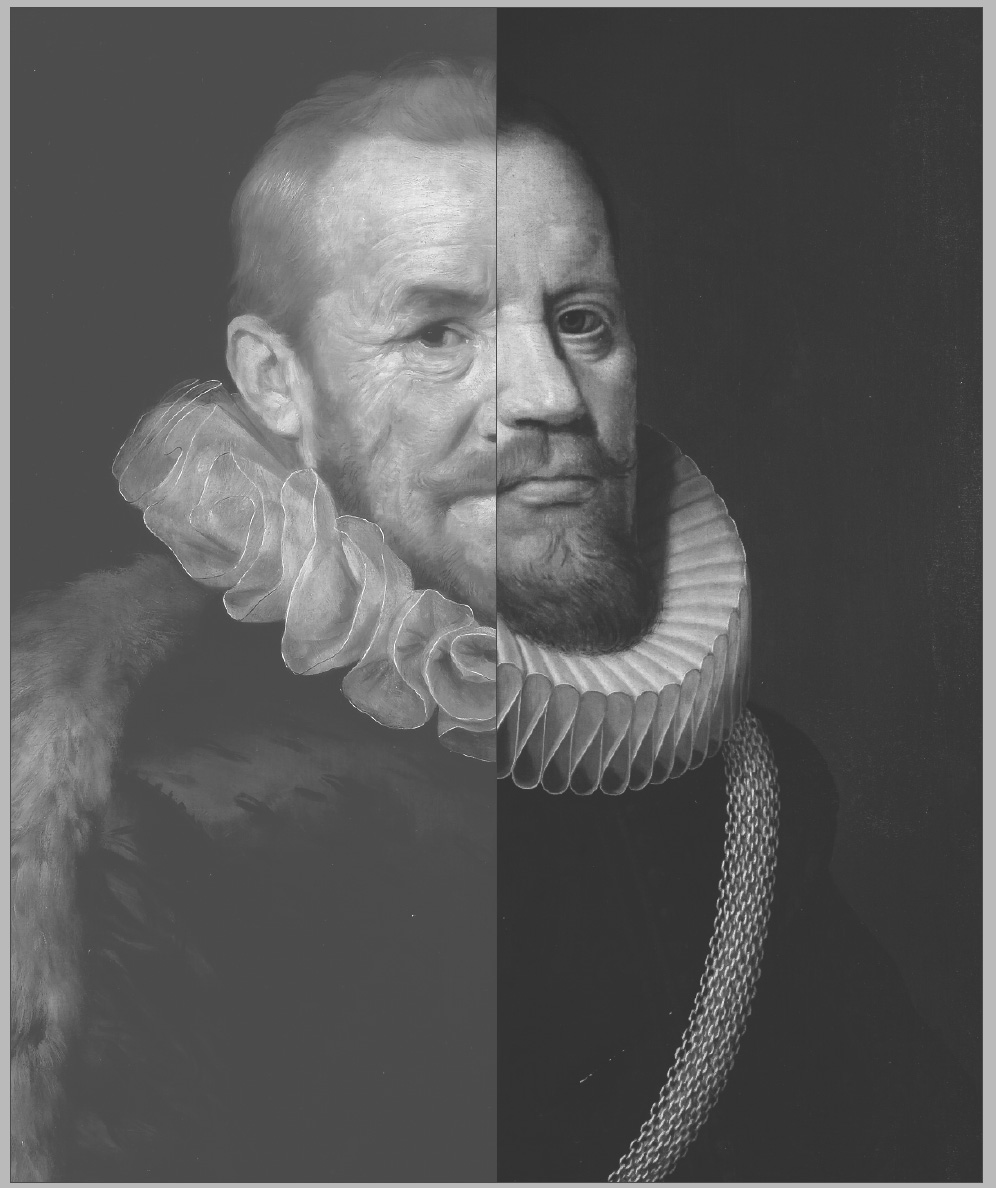

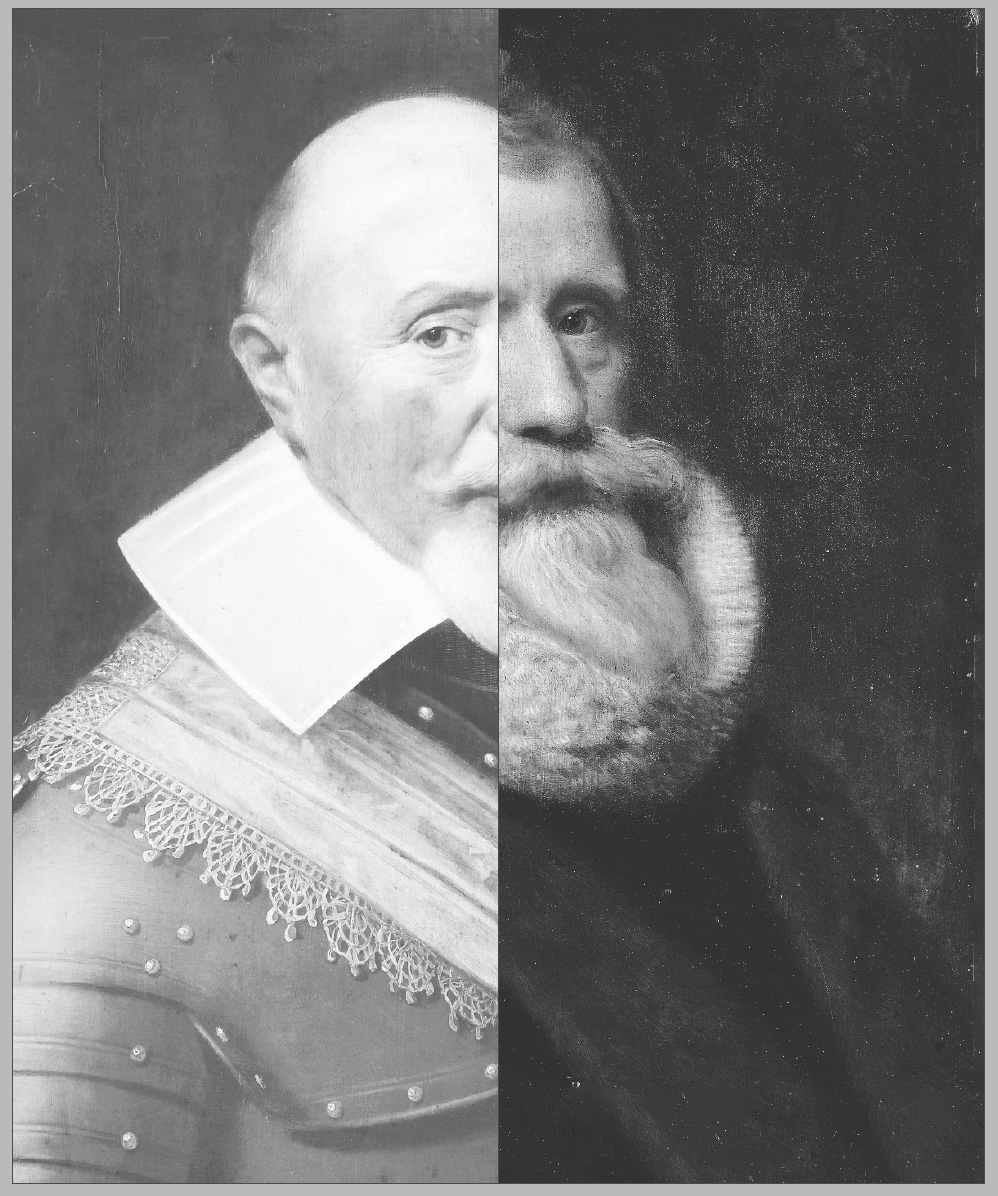

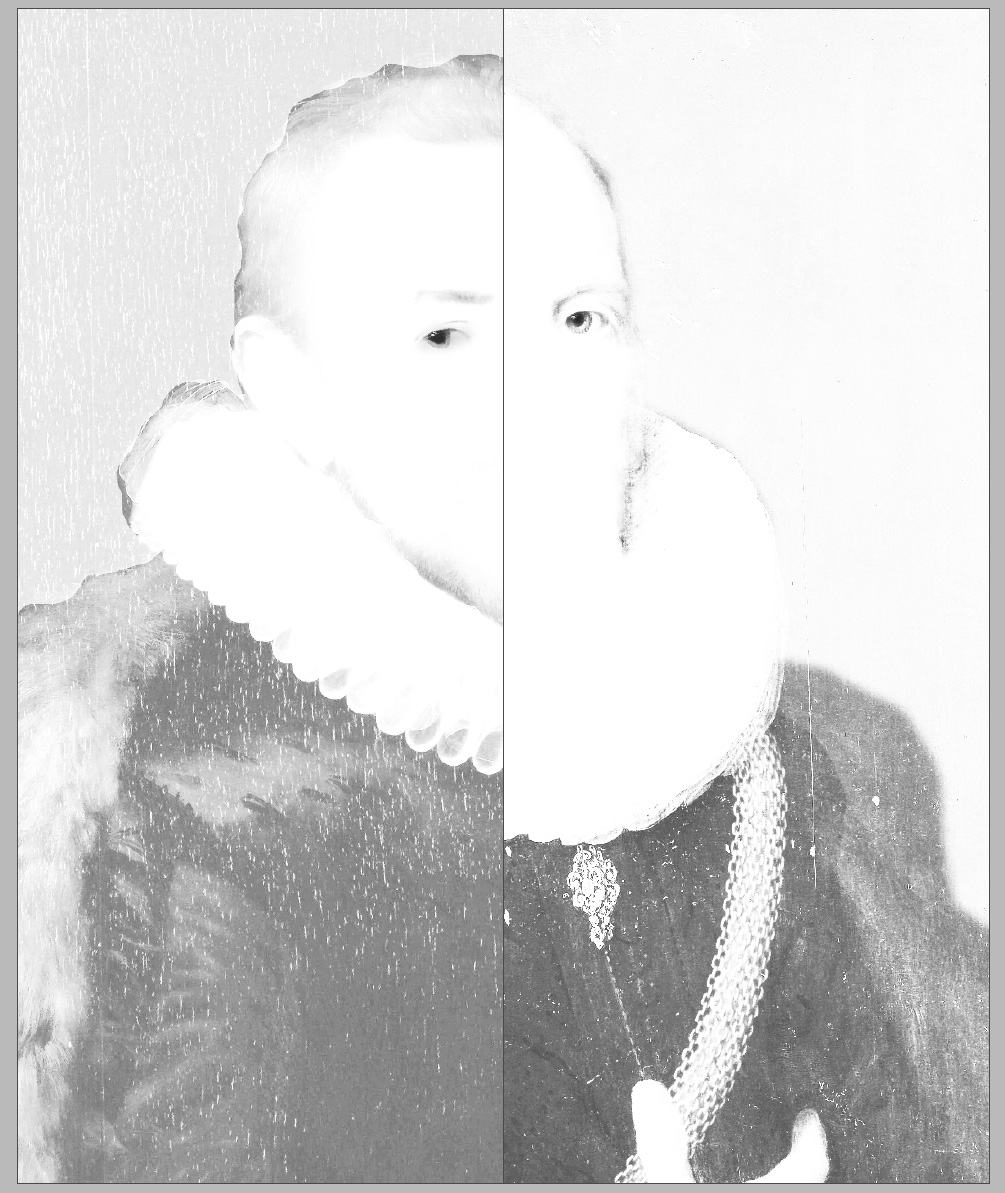

My strategy was to color-separate the high-resolution files downloaded from the Rijksmuseum and then to recombine the images of these objects, to create representations that do not illustrate any one thing—an illusion of inchoate, but richly crafted, possessions. The introductory section of the book presents the charter of the VOC and reveals some of the conflict surrounding the Dutch presence in the East Indies in the form of contemporaneous title pages; subsequent sections of the book suggest the resultant wealth this colonial project produced. The final section of the book presents chimerical portraits—images of affluent Dutch people from the 17th century, recombined to make composite images of people who never existed—that are then overprinted with engravings from the 17th century that document some of the violence associated with the VOC.

I imagined this project as a museum catalog gone completely wrong: reproductions mangled, images misregistered, odd fragments recombined from wildly different sources, cropped badly, with colors transformed into something from a hallucination. I imagined that in this catalog all text—including the vitally important informative, contextualizing captions for the images—would be removed. Gone would be the gallant, abridged histories provided by any museum, normally present in the image descriptions, but now entirely absent. The reader would be left to construct their own narrative from this unreal evidence.

And my hope is that the evidence of this museum catalog is so unreliable, so tainted by its own distorted agenda, that the reader is left with nothing other than a vague impression of a horrific cataclysm swimming around illusory objects of great beauty, virtue, and price.

Unseparated images from pages 76-77. This spread was printed in Pantone 801, Pantone 806, Pantone 810, and two different black inks.